TRANSAT DIARY: ARRIVING IN THE CARIBBEAN

Words by Lydia Paleschi

When I first heard about people crossing oceans by sail, I thought it sounded far-removed from the life I was living. I was intrigued, but I thought it was something I’d never be able to do. I didn’t know how to sail and I knew nothing about boats. So, as we approached the Caribbean after nineteen days at sea, having crossed the Atlantic Ocean, I couldn’t help but reflect on how I’d got there and how I’d managed to do something which previously seemed to be almost out of the realm of possibility. I was also surprised to feel a resistance to setting foot on land again. I had become intoxicated with a clarity of mind which I have yet to discover anywhere other than being at sea, and with the sense of freedom I felt from spending almost three weeks immersed in nature and unbothered by the rest of the world. I reflected, that if I hadn’t pushed myself out of my comfort zone and embarked upon this adventure, I might never have been fortunate enough to discover those same feelings.

Completing a transatlantic crossing

My first Transatlantic crossing involved 2,800 miles of sailing onboard Heaven’s Door – a 50 ft catamaran – with the owner of the boat (Jem) and three other crew (Pim, Naomi and Aisha). The crossing was beautiful. Other than a broken arch support on day three, which meant we could no longer use the main sail, we had a smooth passage from La Palma to Grenada. Our average speed over ground was 6.5 knots and the trade winds blew us generously west, filling up the genoa (foresail) and pushing us downwind. The wind speed ranged from around 15 to 25 knots for the entirety of the journey, and we hardly had to trim the sails. With so many crew, our watch shifts – patterns of three hours on, twelve hours off – were completed easily, especially given that the ocean had been so kind to us.

Golden hour whilst crossing the Atlantic.

As we neared the Eastern Caribbean chain, the volcano of St Vincent emerged from the ocean – first little more than a teardrop on the horizon, later growing into an impressive green peak as we sailed closer. I could feel an excitement bubble up within me and my resistance to arriving on land began to disappear. All the while, I was processing that I’d overcome my latest challenge and that it had more than lived up to my expectations. I thought back to a day several weeks before leaving Cornwall, when I had been frantically journaling my anxieties and fears for the trip ahead, wondering if spending time isolated from the rest of the world with people I didn’t know was something I was capable of. The night we arrived, as I lay in my cabin at anchor, I realised that my fears couldn’t have been further from reality. Not only had I completed the crossing in one piece, but I had arrived with a group of new friends, with whom I’d shared some of the most fulfilling moments of my life so far.

Here’s an excerpt from my journal on 19th December 2021, describing how I felt and what I could see as we prepared to make landfall.

The crew (L to R): Jem (Captain), Naomi, Aisha, Pim and Lydia (front).

07:00 Thank you, Neptune

It was bright again last night. The full moon moved across the sky, lighting the surface of the water as it travelled from the stern over Heaven’s Door, towards the bow. This morning as my night watch came to an end, it was sat low in the sky on the starboard side, whilst the sun rose from behind in the east.

We’re noticing more birds this morning, tell-tale signs we’re getting closer to the land. Boobies have begun to fly around the boat, their brown wings and smooth feathers almost within touching distance. By 7am, the shadowy mound of St Vincent appears, 15 miles in the distance. We drink a shot of rum to celebrate the end of the crossing, before throwing one overboard — our libational offering to Neptune. It feels exciting but also strange to near the end of my first Transat, something which previously seemed such a big challenge in my head.

As we cross the continental shelf, more little islands belonging to St Vincent and the Grenadines make themselves visible – each one deposited there by Kick’em Jenny, an underwater volcano which remains active. We’re careful to avoid the one-mile exclusion zone which surrounds its crater and it feels unusual to have obstacles to sail around, after being surrounded by nothing but open water for so long.

Moonrise over the Atlantic. Pim Pouillot-Chevara.

12:00 Entering the tropics

We’ve had to divert our course on the approach to the island because of a big square rigged five-masted cutter. Even though they’re on our port side, they called on the VHF and requested we give them right of way, much to Jem’s annoyance. I don’t mind though, as it adds to the atmosphere of the approach and reminds me of the Caribbean’s history, which I’ve had plenty of time to read about on the way over. It makes me think of all the colonial boats and trade ships which would have occupied these waters in past centuries – when European colonists would arrive to sell goods and people (mostly from West Africa) and force them to work the land in brutal conditions. It reminds me of how lucky I am and of how recently Grenada has gained its independence (1974) after years of being occupied by the British and the French.

Once the cutter has passed in front of us – the sight of it nothing short of spectacular – we sail above the tip of Carriacou, a small island making up the northernmost part of Grenada’s territory. The sea state transitions and the waves calm, because we’ve passed from the Atlantic Ocean into the shelter of the Caribbean Sea. We’re sailing towards the southern end of Grenada’s main island, where we will anchor for the night outside of Port Louis. Flying fish glide just above the surface of the ocean, a flash and a shimmer of silver, before hitting the water and bouncing off in a confusion of directions. Reams of brown sargassum float past the hulls, their small air sacs keeping them afloat, reminding me of bladder wrack.

Five-masted cutter in the Caribbean Sea. Pim Pouillot-Chevara.

14:00 Getting a closer look

As we near the land and sail along Grenada’s western coastline, we scramble onto the deck to get a closer look. We can see a series of mountains, rising and falling to make up the island’s interior, which is covered in bright green tropical forest. I get a whiff of vegetation — a welcome smell that it feels like I haven’t experienced in a lifetime – plus, the heady scent of smoke coming from small, controlled fires within the woodland. Soon, my nostrils begin to feel overwhelmed with the combination, after smelling nothing but the ocean for weeks.

As I fix my gaze on the landscape, I spot a small smattering of colourful houses and a red and white metal construction, perhaps an electrical tower. It feels luxurious to have something new to feast my eyes upon and Pim and I use the zoom on our camera lenses to get a closer look. There’s a small beach, with tiny makeshift huts on the pale sand. They’re shadowed by long-leaved coconut palms which stand forward from the thicker vegetation of the forest. The green here seems brighter than I can remember seeing before and we laugh when Pim suggests it may be because all we’ve seen is blue for the last three weeks. Arriving to such a thriving and healthy landscape makes me feel excited for what I’m going to discover in the Eastern Caribbean. It’s flourishing and no pictures can prepare you for how beautiful it is.

Pim using her camera to get a closer look at the Grenadian coastline.

21:00 At anchor

After anchoring outside of Port Louis Marina – the flickering lights shining onto the black water in front of Heaven’s Door – we eat our first meal without the roll of the ocean and begin to relax. It’s been an easy journey compared to the crossing from Southampton to Lanzarote, but not without responsibility, broken sleep patterns and the constant anticipation of something going wrong (as it always does when at sea). It’s nice to have nothing to think about and I can feel my body tiring quickly as it releases from being on constant alert. We finish our meal and Jem goes to bed – the tiredness that comes with being skipper finally overwhelming him.

The rest of us take the opportunity to strip off and go for a skinny dip, swimming around the dual hulls of the boat. It’s pitch black and I feel a pang of fear of what may be lurking in the water. A fear of the unknown. I pause, but overcome it quickly when I place it in perspective with the journey we’ve just completed. We attach a flashlight to the deck to give us some visibility and leap from the sugar scoop into the darkness. As we swim from the stern to the bow and back again, tiny fish jump out of the water and we laugh as they splash in front of our faces. After we finish the lap, I dry off and go to bed, feeling grateful to have shared that small moment of celebration with my friends. I think back to when my mind was shrouded in doubt before leaving Cornwall and realise that I’m capable of achieving much more than I ever imagined •

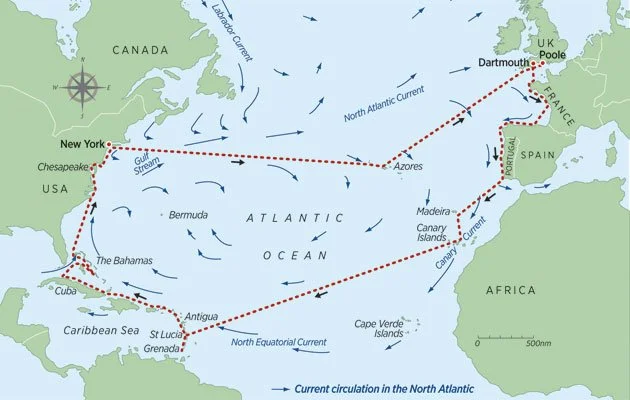

Our route from La Palma to Grenada was similar to the bottom line on this map from Yachting Monthly.

Like to follow my adventures? Sign up to my newsletter so that you don’t miss a blog.

Want to work with me? Get in touch for more information on my freelance writing services.